SHAH ALAM, Sept 12 — Under the twin pressures of rising living costs and shifting social values, Malaysia faces an increasingly severe population challenge: more Malaysians are choosing to marry late, remain single, or forgo having children.

This trend cuts across all major communities, with fertility rates projected to decline among the Bumiputera, Chinese, and Indian groups in the coming decades as the nation moves towards an ageing population.

According to the Statistics Department’s (DOSM) Population Projection 2020-2060 report, Malaysia’s population is expected to grow steadily and peak at 42.38 million in 2059, but the growth rate will slow sharply from 1.7 per cent in 2020 to just 0.1 per cent by 2060.

The steepest decline is expected among the Malaysian Chinese, from 23.2 per cent in 2020 to 14.8 per cent in 2060, while Malaysian Indians will shrink from 6.7 per cent to 4.7 per cent.

Although the Bumiputera community is expected to grow from 69.4 per cent to 79.4 per cent, the average family size is expected to continue shrinking.

For many, getting married and starting a family has become a “luxury choice”, but the issue is no longer just personal — it is now a major concern with far-reaching implications for the economy, education, workforce structure, and the long-term sustainability of the country.

The Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies’ academic committee director Chang Yun Fah said economic pressures, changing family structures, fading traditional values, and insufficient policy support are among the reasons youth across ethnicities are choosing not to marry or have children.

The Taylor’s University associate professor said that, unlike in the past, where marriage and having kids were seen as natural milestones, modern society views them as non-essential choices that must be heavily weighed against financial and practical realities.

Most young people today consider parenthood only if they have family support for childcare, employers that provide flexible working arrangements, and sufficient government aid — conditions that are often unmet.

“For dual-income families, the most immediate question is: ‘Who will take care of the child?’,” he told Media Selangor.

Fertility declines with late marriage

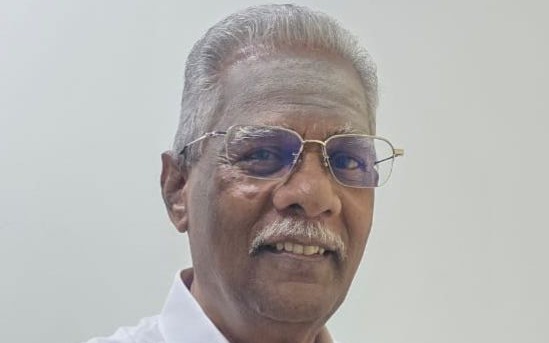

For the Indian community, former Hindu Sangam president Nagappan Arumugam said a major reason for its shrinking population is late marriage.

The Yayasan Falsafah dan Institusi Saiva chairman said that many delay marriage to save money, secure high-paying, prestigious jobs, pursue higher education, and purchase assets like houses and cars to attain better social standing.

As a result, many youth today are getting married only after the age of 30, which often leads to childbearing difficulties due to health factors as fertility rates decline.

He said that ideally, couples should plan on getting married earlier to increase their chances of having children and building larger families.

Not just Malaysia

According to Chang, Malaysia is not alone in facing this challenge. Many countries are grappling with a population crisis where birth rates have fallen below death rates, including South Korea (0.8) and Singapore (0.9).

“To maintain a stable population size, the replacement fertility rate — average number of children a woman should have — should be at least 2.1. However, all ethnic groups in Malaysia fall far below this line.”

Even in countries like Singapore, where extensive policies, including baby bonuses, parental leave, and childcare subsidies, are in place, the impact has been limited. Malaysia, with its comparatively underdeveloped support systems, faces even greater challenges.

“The bigger issue is not people refusing to have children, it is that many no longer want to get married,” he said, adding that there is a need to rebuild a healthier environment for dating and marriage to reverse low birth rates.

“Marriage is a precondition for childbirth, not a mandate to have children,” Chang said.

Policy, mindset changes

Beyond policy incentives, he believes a shift in mindset is equally vital, with many young people today no longer seeing children as a form of future security and rejecting the traditional idea of raising children to care for the elderly.

“We need to reinterpret what it means to ‘raise children for old age’, not as financial dependency, but as emotional companionship,” Chang said.

He urged the older generation to plan for their own retirement and avoid becoming a burden to their children, thereby easing the psychological pressure young people face about starting families.

Chang noted that Selangor could serve as a model for other states, having taken a proactive approach by introducing a range of fertility and elderly welfare initiatives such as the Iltizam Anak Selangor programme, senior citizen shopping vouchers, and bereavement support.

However, these programmes are often poorly promoted, especially within urban and Chinese communities, leaving many unaware of their existence and causing the benefits to go underutilised.

If the fertility rate continues to fall, he said the government should consider phasing in an immigration policy that could help balance the population structure, but cautioned this may invite complex, sensitive matters, from ethnic composition and social integration to foreign labour and talent migration, all of which must be carefully assessed.

Meanwhile, Nagappan urged the government to roll out initiatives to improve the quality of life for Indian youth, especially to encourage marriage and family-building.